This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Thanks to the incredibly talented community of threat researchers that participated in LabyREnth, the Unit 42 Capture the Flag (CTF) challenge. Now that the challenge is closed, we can finally reveal the solutions of each challenge track. We’ll be rolling out the solutions for one challenge track per week. Next up, the Unix track.

Unix 1 Challenge: Layers upon layers of _____s of wisdom.

Challenge Created By: Richard Wartell @wartortell

We are given a perl script that when executed tells us we are doing a thing and then says stahp.

$perl bowie.pl

You're doing a thing...

AAAA

stahp

If we look at the script source, we can see that it has a series of nested if else conditions. At each layer, the script requests user input which it uses for the next if condition. If the if conditions are true, an additional base64 chunk is decoded and appended to the $a variable.

print "You're doing a thing...\n";

my $input = <STDIN>;

$input = trim($input);

if ($input eq (chr(5156 - 5035) . chr(-4615 - -4716) . chr(3162 - 3047))) {

$a = $a . MIME::Base64::decode("…”)

This repeats many times until the last if condition which evals a base64 block.

eval MIME::Base64::decode("…”)

We can use python to base64 decode each of these blocks ourselves. When we decode the eval block it has a block that is decoded and appended to the ‘$a’ variable and another block that is eval’d. This repeats over and over many times. If we grab each block that appends to the ‘$a’ variable, decode them, and write them to a file, we find that it is a jpg and contains the key.

from base64 import b64de

a = b64decode("R0lGODlh2

a = a + b64decode("KmZRg

…

a = a + b64decode("7w3jz

f = open("out.gif", "w")

f.write(a)

When I was working the challenge, I manually kept decoding each block and writing it until I got enough of the picture for the key.

Jeff White solved the entire solution with a bash one liner that is a thing of beauty.

cp bowie.pl bowie_1 && for i in $(seq 1 50); do grep -E "\$a|eval" bowie_$i |cut -d"\"" -f2 |base64 -D > bowie_expr $i + 1 ; done && for i in $(grep "\$a" bowie_1 |cut -d"\"" -f2); do echo $i |base64 -D >> bowie.gif; done && for i in $(find . -size +2k -ls |cut -d"/" -f2 |grep -vE "bowie_1$|bowie.pl" |sort -t _ -k 2 -n); do grep "\$a" $i |cut -d"\"" -f2 |base64 -D >> bowie.gif; done && rm bowie_* && open bowie.gif && echo "D4rkCryst4lz"

Unix 2 Challenge: Melted cowboys and space wrestling; this isn't the Ninth Wonder of the World. Maybe because we're all a little rusty.

Challenge Created By: Anthony Kasza @anthonykasza

We are given a 64bit ELF challenge binary.

$file challenge

challenge: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=4570af615de39c4912c17a09f9fbf8419368572b, not stripped

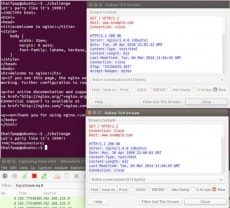

We start off by running it and see a message that says, “Let’s party like it’s 1999!” and then the html contents of example.com.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 |

./challenge Let's party like it's 1999!! <!doctype html> <html> <head> <title>Example Domain</title> <meta charset="utf-8" /> <meta http-equiv="Content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" /> <style type="text/css"> body { background-color: #f0f0f2; margin: 0; padding: 0; font-family: "Open Sans", "Helvetica Neue", Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif; } div { width: 600px; margin: 5em auto; padding: 50px; background-color: #fff; border-radius: 1em; } a:link, a:visited { color: #38488f; text-decoration: none; } @media (max-width: 700px) { body { background-color: #fff; } div { width: auto; margin: 0 auto; border-radius: 0; padding: 1em; } } </style> </head> <body> <div> <h1>Example Domain</h1> <p>This domain is established to be used for illustrative examples in documents. You may use this domain in examples without prior coordination or asking for permission.</p> <p><a href="http://www.iana.org/domains/example">More information...</a></p> </div> </body> </html> |

I perform stings on the binary and see some interesting ones related to dates, example.com, and rust.

…

http://www.example.com

stream did not contain valid UTF-8

1/1/1999%d/%m/%Y

This system is obviously not a 90's kid.1/1/2000Possible Y2K issue.

What year is it?!

%a, %d %b %Y %H:%M:%S GMT

That Date isn't RFC compliant

That response was not OK

Let's party like it's 1999!!

…

rust_builtin.c

rust_begin_unwind

rust_eh_personality

rust_eh_personality_catch

…

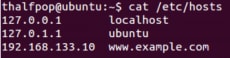

Next we open it up and look at it in IDA and after demangling the names, we can see a pretty large main function. We can start by using IDA’s cross references on some of those interesting date strings we found earlier. We see that an http request is made to www.example.com and the headers are checked for the date. This gives us a pretty good idea of what we can try to fiddle with.

I setup an Ubuntu virtual machine on a private virtual network and then created another linked clone to have a server. I changed the hosts file on the client system to point www.example.com to the other server system. I also installed nginx on the server system to have an easy http listener.

I tried to run the program with the current date and it printed out the nginx response and then I changed the date back to 1999 like the challenge asks and it printed out the key.

PAN{ThaddeusVenture}

Unix 3 Challenge: Far above the world sitting in your tin can the stars look very different today

Challenge Created By: Tyler Halfpop @0xtyh

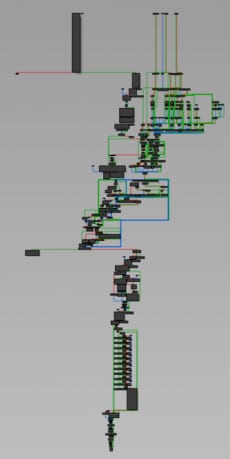

We are given an ELF file and when it runs, it draws a nice cat.

When we open it in IDA and go to graph mode in the main function, we can see the key drawn by the nodes.

The binary was constructed using the REpsych framework by @xoreaxeaxeax.

Unix 4 Challenge: Sometimes you find treasure in the oddest of places...

Challenge Created By: karttoon @noottrak

We receive this beautiful image to start with.

I opened the image with my favorite hex editor, 010Editor, and I could see there is a large blob at the end of the image after the FF D9 ending of the jpg.

I extracted the blob and divided the sections that were separated by tags. There was a coppertunnel, goldtunnel, silvertunnel, and a crystal tunnel. Each section looked like base64, but the padding was at the beginning with the =. I used 010Editor’s built in Ascii reverse script to reverse the text and then 010Editor’s decode base64 script. It looked like I had backwards base64 again, so I repeated this step several times until I got a PK zip header. I did this procedure for each tunnel getting to the file before the zip file and then I used python to write the final file.

from base64 import b64decode

ci = open("coppertunnel.txt", "rb").read()

co = open("copperout.zip", "w")

co.write(b64decode(ci))

si = open("silvertunnel.txt", "rb").read()

so = open("silverout.zip", "w")

so.write(b64decode(ci))

gi = open("goldtunnel.txt", "rb").read()

go = open("goldout.zip", "w")

go.write(b64decode(ci))

cri = open("crystaltunnel.txt", "rb").read()

cro = open("crystalout.zip", "w")

cro.write(b64decode(ci))

I unzipped the files and saw that I had 4 parts of a Par archive.

treasure.vol306+306 2.par2

treasure.vol306+306 3.par2

treasure.vol306+306 4.par2

treasure.vol306+306.par2

I did some Googling and found MultiPar to work with the files. I was able to use the Repair function to restore a chest.zip file.

Chest.zip was an encrypted zip file, so I started to look for the password in the original image. I tried steghide and it outputted bards_song, which was a text file with excellent instructions that would have been helpful earlier on, and the password for the zip file.

steghide.exe extract -sf labyrinth_entrance.jpg

Enter passphrase:

wrote extracted data to "bards_song".

Over the hills and through the grass

By dawn of light in the mountain pass

The goblins treasure awaits the steadfast

Walking in REVerse, the eye opens as you go past

A smell leads you onward, luring you to follow

At the end of each tunnel, a PARt of treasure in the hollow

Combine them to find a door hidden by rhyme

Opened once with the words "aintnobodygottime"

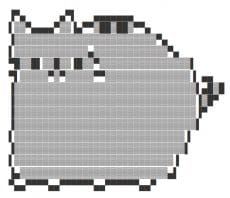

I was then able to unzip the chest.zip, which gave me a MachO called jareths_maze. I ran it in a VM and I was greeted with this horrifying ascii art.

I couldn’t let the clowns win, so I had to open the file in IDA. I decompiled main and there were more clowns, but the message was different.

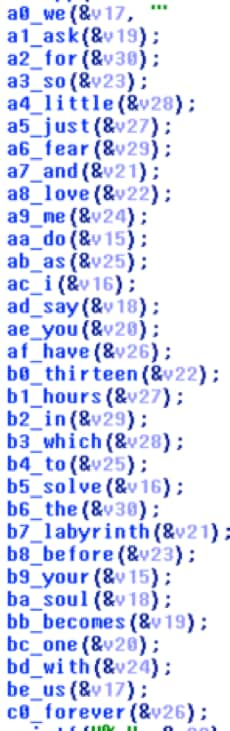

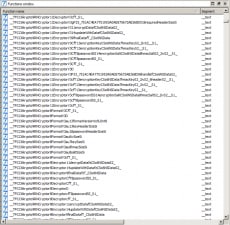

Then I saw this demoralizing string of function names and I started to get a little freaked out.

The program printed the ascii art after going through these functions. I knew that the beginning message wasn’t correct and the ending message wasn’t correct. Each function was overwriting a character in the message and the a group of functions was being overwritten by what the b group of functions was writing.

I used IDA to jump into each function and grab the ordinal of the character that the message was supposed to be with the a functions and then I used python to convert the ordinal to the character to obtain the key.

PAN{D4nKkry5t4l}

Unix 5 Challenge: All your filez are belongz to us.

Challenge Created By: Tyler Halfpop @0xtyh

We are given a binary called krypto.danger, and if we run file on it, we can see that it is a 64bit Mach-O.

file krypto.danger

krypto.danger: Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64

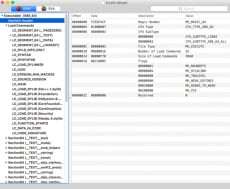

A good first step when examining a Mach-O is to check it out in osxreverser’s branch of MachOView to examine the various Mach-O header information and strings, much like you would with a PE file.

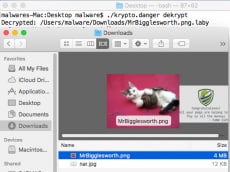

The next step is to run the binary to get a better understanding of what it does. We should run untrusted binaries in a virtual machine, but we are too busy looking at pictures of Mr. Bigglesworth to be bothered by that. When we run it, our picture of Mr. Bigglesworth gets encrypted and a .laby extension is appended. A menacing narwhal also pops up that ironically tells us “Congratulations! All your pngs are belong to us Pay us all the moneyz – PANW GSRT”. Not Mr. Bigglesworth! This is war.

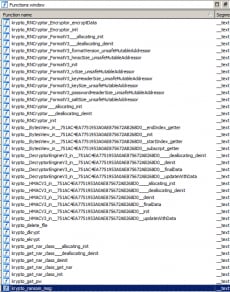

When we open the binary in IDA we can see all the ugly mangled Swift names.

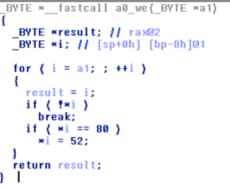

We can use an IDA Script called SwiftDemang to demangle the Swift names to make it easier to read. After running the script, it is a little easier to look at the function names.

After demangling the functions, we can see some interesting functions like krypto_dkrypt and krypto_ekrypt. Krypto_dkrypt gets called if there is a dekrypt argument. Let’s try to use that to see if we can get Mr. Bigglesworth back.

Now that we have Mr. Bigglesworth with us again, we can get back to solving the challenge. The dkrypt and ekrypt functions both call an interesting looking function called get_pw that returns a string we can tell from the comment added by SwiftDemang.

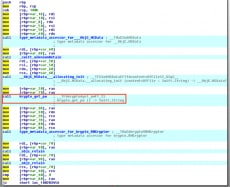

When we look at the get_pw we see an interesting looking string highlighted below and calls to RNCryptor. If we Google RNCryptor, we can find an open source Swift version of AES-256, which is being used to encrypt the password that is then used to encrypt or decrypt the files.

If we setup remote debugging with IDA and break on the return from get_pw, we can see the key to the challenge in the string pointed to by the return value in RAX at 0x100608101.

Unix 6 Challenge: Go forth good language.

Challenge Created By: Richard Wartell (@wartortell)

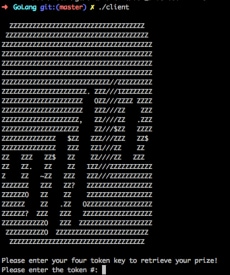

For this challenge, you’re given a server and a client binary, both Mach.O files. If we run the client binary, we can see that it’s asking for a four token key in order to get the “prize”.

Thankfully, these binaries haven’t had their symbols stripped so it’s easy to find interesting functions in the binary. From a quick look at the client library, we can see the strings that were shown above, as well as the client library sending the four tokens you enter to a server:

So we need to look into how the server checks the tokens that are sent. When we open up the server in IDA Pro, we can easily see the functions main_check_key1, main_check_key2, main_check_key3, and main_check_key4 being called in a row. If we following them, there is a check which leads to where the real key would be if this was the actual server:

From here, all we need to do is figure out what each token needs to be. From digging through each of the four functions, we can find the tokens that will get us the key:

- Checks the first message character by character, the token is “3at”

- Checks the second message, the length must be 11, and each character is pairwise compared with each one, the differences can be used to determine the characters. The token is "chInch1ll@z".

- Performs specific checks on the token against another 4 byte string. The token is “H1gh”.

- Compares characters from the token against the string “Fromunda” and the number 183. The token is “F183r”

We know we’ve got the right tokens because we can run the server and client locally, and we get this:

When we connect instead to the IP contained in the directions file and provide the 4 tokens, we get the key:

PAN{th@Nk5_m4r1ha_U_s0_n1c3}

Unix 7 Challenge: Crack the codes to get the Apple

Challenge Created By: Tyler Halfpop (@0xtyh)

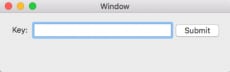

This time I was handed an OSX compiled application called RedDelicious. First, I simply ran it (not smart, but I never claimed to be), and got the following window popup:

So I entered some text into the window and clicked Submit, which gave me the message “Try harder…” From this I assumed that I would have to submit the right key in order to get a success message and hopefully the key for the challenge. So, now I wanted to disassemble the binary and see what happens when I click “Submit”.

In IDA, the first thing I noticed is that most functions start with “__T”, which tells me I’m dealing with a Swift compiled binary, since that is the prefix for all symbols in Swift. Swift is great at making ugly, huge function names, so rather than messing around with demangling them or anything too ugly, I had one lead of the “Try harder…” string from when I entered a wrong key. I looked in the strings window and found references to that function and went back from there:

Then I saw the same function both referencing the strings “Try harder…” and “C0ngr4tz!”, so I knew I was on the right track. The function that references them looks like this:

At the bottom where the code flow splits in two, each path has the same code with a different string reference, so I knew I was in the key check function. Now to figure out how to make it say “C0ngr4tz!”

Swift’s compiler treats variables very similar to C++, passing a reference to “this” as an argument to functions, and then using it to find other class references. The class jump table for this class is NSViewController, found at 0x100008090. We’ll need this in order to fix up the calls used in the function. After cleaning up all of Swift’s object oriented code and Automatic Reference Counting (ARC), we can dumb this function down into some simpler pseudocode:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

check_key: a = entered_key a = bb64(a) a = xxor(a, "av9vex8pocs4id2") a = bb64(a) a = xxor(a, " abracadabra") a = bb64(a) if a == " LyY8TiwwJighJzRSNycvJyU3LzQ1GTc0JlA2ACcGBTcuUSc3JBkZLSoaS1EzUwotBwsDDTQbEiY3Mw0SNDcZVjcLKywjCTpKPApWTw==": label = "C0ngr4tz!" else: "Try harder..." |

This gives us a pretty clear idea of what’s going on, but we’ll have to check each of these functions to figure out what they do. After analysis, we find that they do the following different functions:

- bb64 – Base64 encode the passed in argument

- xxor – XOR the passed string with the provided key

So, if we write a quick little python script, we can get the key:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

import base64 def xxor(plain, key): enc = "" for i in range(len(plain)): enc += chr(ord(plain[i]) ^ ord(key[i % len(key)])) return enc a = "LyY8TiwwJighJzRSNycvJyU3LzQ1GTc0JlA2ACcGBTcuUSc3JBkZLSoaS1EzUwotBwsDDTQbEiY3Mw0SNDcZVjcLKywjCTpKPApWTw==" a = base64.b64decode(a) a = xxor(a, "abracadabra") a = base64.b64decode(a) a = xxor(a, "av9vex8pocs4id2") a = base64.b64decode(a) print a |

And the key is: PAN{My_m0th3r_told_m3_2b3_w4ry_of_F@uns}

Leave a comment below to share your thoughts about the Unix track challenges. Be sure to also check out how other threat researchers solved these challenges:

Unix Challenge 1

- https://irq5.io/2016/08/17/labyrenth-2016-write-up-bowie-pl/

- https://github.com/uafio/git/blob/master/scripts/labyREnth-2016/labyrenth-2016-unix-1.py

Unix Challenge 3

Unix Challenge 5

Unix Challenge 6

- http://www.ghettoforensics.com/2016/08/running-labyrenth-unit-42-ctf.html

- https://github.com/uafio/git/blob/master/scripts/labyREnth-2016/labyrenth-2016-unix-6.py

Unix Challenge 7

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.