As a malware reverse engineer, I often find myself using IDA Pro in my day-to-day activities. It should come as no surprise, seeing as IDA Pro is the industry standard (although alternatives such as radare2 and Hopper are gaining traction). One of the more powerful features of IDA that I implore all reverse engineers to make use of is the Python addition, aptly named ‘IDAPython’, which exposes a large number of IDA API calls. Of course, users also get the added benefit of using Python, which gives them access to the wealth of capabilities that the scripting language provides.

Unfortunately, there’s surprisingly little information in the way of tutorials when it comes to IDAPython. Some exceptions to this include the following:

- “The IDA Pro Book” by Chris Eagle

- "The Beginner’s Guide to IDAPython” by Alex Hanel

- “IDAPython Wiki” by Magic Lantern

In the hopes of increasing the amount of IDAPython tutorial material available to analysts, I’m providing examples of code I write as interesting use-cases arise. For Part 1 of this series, I’m going to walk through a situation where I was able to write a script to thwart multiple instances of string obfuscation witnessed in a malware sample.

Background

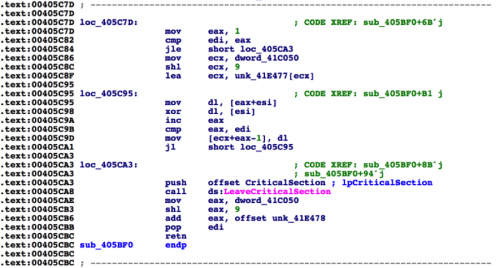

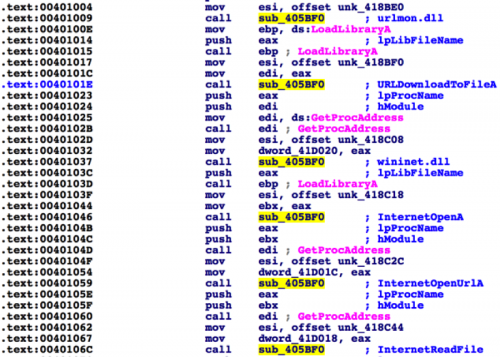

While reverse-engineering a malicious sample, I encountered the following function:

Figure 1 String decryption function

Based on experience, I suspected this might be used to decrypt data contained in the binary. The number of references to this function supported my suspicion.

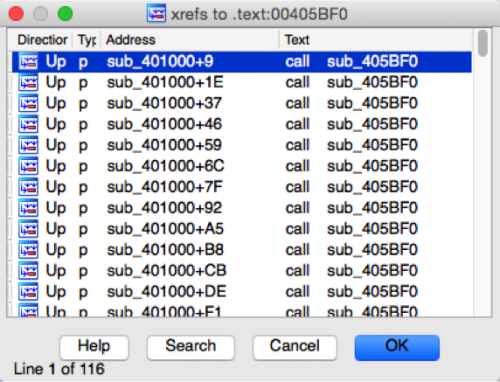

Figure 2 High number of references to suspect function

As we can see in figure 2, there are 116 instances where this particular function is called. In each instance where this function is called, a blob of data is being supplied as an argument to this function via the ESI register.

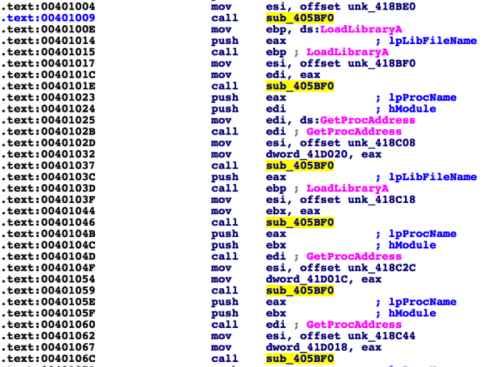

Figure 3 Instances where the suspect function (405BF0) is called

At this point I am confident that this function is being used by the malware to decrypt strings during runtime. When faced with this type of situation, I typically have a few choices:

- I can manually decrypt and rename these obfuscated strings

- I can dynamically run this sample and rename the strings as I encounter them

- I can write a script that will both decrypt these strings and rename them for me

If this were a situation where the malware was only decrypting a few strings overall, I might take the first or second approach. However, as we’ve identified previously, this function is being used 116 times, so the scripting approach will make a lot more sense.

Scripting in IDAPython

The first step in defeating this string obfuscation is to identify and replicate the decryption function. Fortunately for us, this particular decryption function is quite simple. The function is simply taking the first character of the blob and using it as a single-byte XOR key for the remaining data.

E4 91 96 88 89 8B 8A CA 80 88 88

In the above example, we would take the 0xE4 byte and XOR it against the remaining data. Doing so results in the string of ‘urlmon.dll’. In Python, we can replicate this decryption as such:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

def decrypt(data): length = len(data) c = 1 o = "" while c < length: o += chr(ord(data[0]) ^ ord(data[c])) c += 1 return o |

In testing this code, we get the expected result.

|

1 2 3 4 |

>>> from binascii import * >>> d = unhexlify("E4 91 96 88 89 8B 8A CA 80 88 88".replace(" ",'')) >>> decrypt(d) 'urlmon.dll' |

The next step for us would be to identify what code is referencing the decryption function, and extracting the data being supplied as an argument. Identifying references to a function in IDA proves to be quite simple, as the XrefsTo() API function does exactly this. For this script, I’m going to hardcode the address of the decryption script. The following code can be used to identify the addresses of the references to the decryption function. As a test, I’m simply going to print out the addresses in hexadecimal.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

for addr in XrefsTo(0x00405BF0, flags=0): print hex(addr.frm) Result: 0x401009L 0x40101eL 0x401037L 0x401046L 0x401059L 0x40106cL 0x40107fL <truncated> |

Getting the supplied argument to these cross-references and extracting the raw data proves to be slightly more tricky, but certainly not impossible. The first thing we’ll want to do is get the offset address provided in the ‘mov esi, offset unk_??’ instruction that proceeds the call to the string decryption function. To do this, we’re going to step backward one instruction at a time for each reference to the string decryption function and look for a ‘mov esi, offset [addr]’ instruction. To get the actual address of the offset address, we can use the GetOperandValue() API function.

The following code allows us to accomplish this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

def find_function_arg(addr): while True: addr = idc.PrevHead(addr) if GetMnem(addr) == "mov" and "esi" in GetOpnd(addr, 0): print “We found it at 0x%x” % GetOperandValue(addr, 1) break Example Results: Python>find_function_arg(0x00401009) We found it at 0x418be0 |

Now we simply need to extract the string from the offset address. Normally we would use the GetString() API function, however, since the strings in question are raw binary data, this function will not work as expected. Instead, we’re going to iterate byte-by-byte until we reach a null terminator. The following code can be used to accomplish this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

def get_string(addr): out = "" while True: if Byte(addr) != 0: out += chr(Byte(addr)) else: break addr += 1 return out |

At this point, it’s simply a matter of taking everything we’ve created thus far and putting it together.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 |

def find_function_arg(addr): while True: addr = idc.PrevHead(addr) if GetMnem(addr) == "mov" and "esi" in GetOpnd(addr, 0): return GetOperandValue(addr, 1) return "" def get_string(addr): out = "" while True: if Byte(addr) != 0: out += chr(Byte(addr)) else: break addr += 1 return out def decrypt(data): length = len(data) c = 1 o = "" while c < length: o += chr(ord(data[0]) ^ ord(data[c])) c += 1 return o print "[*] Attempting to decrypt strings in malware" for x in XrefsTo(0x00405BF0, flags=0): ref = find_function_arg(x.frm) string = get_string(ref) dec = decrypt(string) print "Ref Addr: 0x%x | Decrypted: %s" % (x.frm, dec) Results: [*] Attempting to decrypt strings in malware Ref Addr: 0x401009 | Decrypted: urlmon.dll Ref Addr: 0x40101e | Decrypted: URLDownloadToFileA Ref Addr: 0x401037 | Decrypted: wininet.dll Ref Addr: 0x401046 | Decrypted: InternetOpenA Ref Addr: 0x401059 | Decrypted: InternetOpenUrlA Ref Addr: 0x40106c | Decrypted: InternetReadFile <truncated> |

We can see all of the decrypted strings within the malware. While we can stop at this point, if we take the next step of providing a comment of the decrypted string at both the string decryption reference address and the position of the encrypted data, we can easily see what data is being provided. To do this, we’ll make use of the MakeComm() API function. Adding the following two lines of code after our last print statement will add the necessary comments:

|

1 2 |

MakeComm(x.frm, dec) MakeComm(ref, dec) |

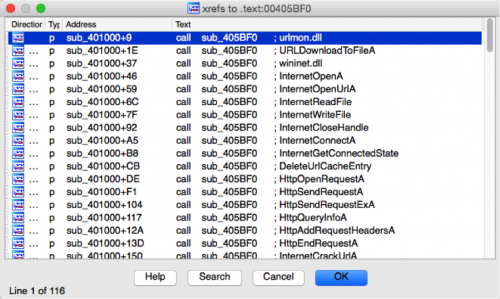

Adding this extra step cleans up the cross-reference view nicely, as we can see below. Now we can easily identify where particular strings are being referenced.

Figure 4 Cross-reference to string decryption after running IDAPython script

Additionally, when navigating the disassembly, we can see the decrypted strings as comments.

Figure 5 Assembly after IDAPython script is run

Conclusion

Using IDAPython, we were able to take an otherwise difficult task of decrypting 161 instances of encrypted strings in a malicious binary and defeat the binary quite easily. As we’ve seen, IDAPython can be a powerful tool for a reverse engineer, simplifying various tasks and saving precious time.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.