This is the second part of our series on “connecting the dots,” where we investigate ways to link attacks together to gain a better understanding of how they are related. In Part 1, we looked at how domain WHOIS information can be used to identify connections between malicious domains and potentially the actors who own them. In Part 2 we dive into Passive DNS (PDNS), which allows analysts to look back in time and discover how a domain has been used in the past.

Why Passive DNS?

Before we jump into PDNS, we need to understand DNS, or the Domain Name System. DNS is often described as the phonebook of the Internet (For our younger readers who may be wondering what a phonebook is, Wikipedia can explain.) Rather than ask users to remember individual IP addresses, DNS instead maps numerical addresses to easy-to-remember domain names, much like a person’s name might be associated with a specific phone number. So instead of memorizing that Google hosts their search engine on 65.199.32.22, you simply need to remember www.google.com. The system solved an enormous usability issue at the onset of the Internet, but unfortunately left room for abuse as well.

Unlike a paper phonebook, which remains static until a new version is published, DNS allows for constant dynamic updates that allow the system to be more flexible. Domain name owners can update their Domain-> IP mapping as often as they like and users will always be able to get the correct results because the lookups are dynamic.

When your computer needs to find the IP address associated with a domain, it sends a query to a recursive DNS server, which reaches out to a series of DNS servers to retrieve a response. A DNS response contains an answer to the query, which contains the information your computer needed. Below is a simplified answer for a query for www.google.com.

www.google.com A 65.199.32.22

First we have the queried name, followed by “A” the record type, and finally an IPV4 address which Google has associated with the domain. This answer is good for a set period of time (known as a time to live or TTL), which can be days or longer, but is often quite short.

As the system is dynamic, the mapping of a domain to an IP is ephemeral; there’s no way for a DNS server to tell you what IP address a domain name resolved to five minutes ago, let alone five years ago. Additionally, there’s no way to perform the reverse mapping, where one can find all of the domain names that have resolved to a specified IP address. Passive DNS was introduced to solve these and other problems with investigating DNS abuse.

How PDNS Works

PDNS was created in 2004 by Florian Weimer and introduced widely at the FIRST conference in 2005. The technology is a fairly simple concept: a network device (sensor) captures all DNS answer messages and forwards them into a central database that logs the relevant information, the queried domain, the answer and a timestamp of when the request occurred. This creates a historical index of IP to domain and domain to IP mappings that have occurred on the monitored network.

The fact that the database only contains information from the network your sensor monitors is one of the major challenges for users of PDNS. Unless the data from these systems is melded into a single query interface, the analysts using them will have different data sets. If a domain has never been queried inside your network, you’ll have no data on it at all. There are multiple partial solutions to this problem, which we’ll discuss in later sections.

What can PDNS do for you?

For an intelligence analyst, making a connection between two components in an attack can provide new insight into an investigation. You may find that two previously unlinked attacks actually share a command and control server, or find out about infrastructure that may have been used in attacks you have not yet discovered.

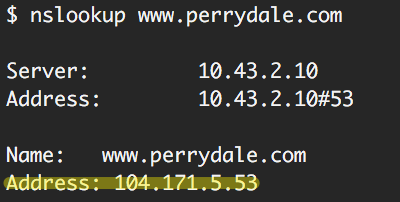

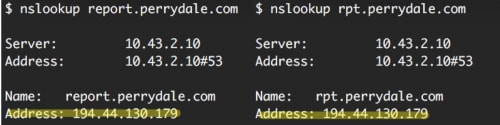

In July 2015, we published an article describing an attack on the US government by an APT group known as UPS a.k.a. APT3. Our data showed that two subdomains of a seemingly legitimate website, rpt.perrydale[.]com and report.perrydale[.]com had been involved in the attack. DNS queries for these subdomains compared to the legitimate “www” domain (www.perrydale[.]com) revealed that “www” was hosted on an IP address in the United States, where the other subdomains mapped to an IP address in Ukraine.

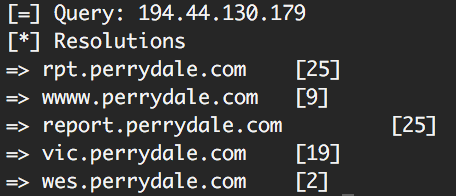

We used PDNS to search for any other domains associated with the Ukrainian IP, which immediately produced three additional subdomains with suspect names (such as wwww) that may have been part of the attack campaign.

Additional analysis was required at this point to confirm these subdomains were also malicious, but PDNS allowed us to discover the fact that these subdomains existed and were associated with a the Ukrainian IP.

PDNS Pitfalls

Now that you have seen the benefits of using PDNS to connect attacks, it’s critical to understand that not every connection is valid.

Here are some of the situations to be weary of when using PDNS to make connections in your analysis.

- Domain Names Change Hands: A domain used in an attack three years ago has likely expired and been re-registered by a completely unrelated entity. This could be a domain name reseller or just a regular individual. You can use WHOIS data to discover when these changes happened, which will help you gauge the validity of these connections.

- IP Addresses Change Hands (and may be shared): In the same way that a domain name can be transferred from one individual to another, IP addresses are often used by many different entities, sometimes at the same moment. This has become especially important in the era of cloud services, where a server can be created and destroyed with the press of a button. Without knowledge of when the IP address was in an actor’s control to back you up, an IP->domain connection may be invalid.

- Sinkholes (and parking websites) are everywhere: In the course of your analysis, you may come across an IP address hosting thousands of domain names. One common scenario is that the domain name has expired and an individual has re-registered it in case someone else purchases it in the future for a higher price. These domains are typically “parked” on a server that states the domain name is for sale, and this IP address should be considered invalid for all connections. The second common scenario is when security researchers create a “sinkhole” to which many previously malicious domain names point in order to collect data. Similar to the parking websites, these sinkholes are not useful for making connections, but should be a clear indication that someone else is investigating your subject.

How can I get started?

As mentioned above, you could run your own passive DNS sensor (like dnslogger), which will give you information about your own network, but that’s only going to show you a small section of the world. Having insight into your own DNS requests is certainly valuable, but from an intelligence perspective you may want a broader view.

There are many PDNS sources on the web, which can be queried to expand the amount of information available, here are just a few:

You may also consider the FarSight Passive DNS service, which aggregates data from a large number of PDNS sensors. Finally, if you want to make your life as easy as possible you should take a look at PassiveTotal, which aggregates many of these sources into a single interface with additional features.

Regardless of how you may choose to implement PDNS in your workflow, it is an important tool to have during intelligence analysis and collection. You can leverage this tool to not only identify active, real time threats, but also begin visualizing and mapping out adversary infrastructure to help answer the questions of who, what, when, why, and how.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.