The 2015 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) represents the first time Palo Alto Networks has contributed data to this important publication, and we are proud to be part of an intelligence-sharing ecosystem that, in the end, raises the collective bar for everyone in the industry.

While reviewing the findings, a few key points stood out to the Unit 42 team:

“70 to 90% (depending on the source and organization) of malware samples are unique to a single organization.”

This important data point means that a single piece of malware could be subtly altered to produce an endless stream of variants, all of which would evade traditional signature-based detection. Of note, this premise matches our recent internal research, lending more credence to this trend.

Verizon defines unique malware from a signature/hash perspective, “when compared byte-to-byte with all other known malware.” In fact, there are a variety of commonly available and easy to use tools that can automate the process of obfuscating these threats. In what has become a mantra throughout the security industry, the report states that, “Signatures alone are dead,” and Palo Alto Networks would agree. When malware is used once (or a handful of times), matching against these patterns has limited effectiveness at best. When taken from a defenders perspective, it is clear that organizations need to consider an approach that can prevent malware based on payload, not signature, and quickly generate and share protections for the endless new variants released each day.

“In 70% of the attacks where we know the motive for the attack, there’s a secondary victim.”

This highlights an important trend: adversaries are using third-party websites, or co-opting infrastructure, to deliver their attacks. This often can mean that the person or organization that experiences the initial breach isn’t the real target, but a tool, a pawn in a larger battle. From an attacker perspective, this allows them to take advantage of trust that these “jump-off” points have built up, or use the resources of another company for their gain.

The most common methods observed in these types of attack are:

- Watering hole attacks (also known as strategic web compromise), where an organization’s website is infected with exploit code to try and infect visitors to their site.

- DDoS attacks, where web servers or other high-bandwidth hosts are compromised and used in an attack on another target.

Anyone who’s ever thought, “My company isn’t a big target” should look at this statistic and realize that they can’t trustingly stand on the sidelines. Either your infrastructure is secured against attack, or it will be “drafted” into one side of the battle.

“99.9% of the exploited vulnerabilities had been compromised more than a year after the associated CVE was published.”

Palo Alto Networks has observed that the extended lifetime of CVE exploitability, and rapid implementation of new vulnerabilities into attack toolkits are nothing new. New vulnerabilities take time, effort and resources to discover – and if you think of adversaries in the context of “running a business,” they want to get the greatest return on their investment (ROI). Generally, there is no need to deploy a zero-day exploit, when an older, and unpatched vulnerability can be used. Well-funded adversaries that have the in-house R&D to discover a new CVE and develop unique exploit code against it are the exception, rather than the rule. When a new CVE is discovered, we typically see them being added to exploit kits in about a month, following initial disclosure and reverse engineering.

It is also important to draw the line between commonly exploited CVEs, and those being used by the most advanced and targeted attackers. In general, the DBIR focuses on exploits targeting web applications, whereas we believe the most advanced and targeted threats leverage memory corruption exploits to gain a foothold on the endpoint. These exploits often come in the form of data files such as PDF or MS Word documents. As traditional anti-virus (AV) products do not detect such exploits, it is difficult to gather statistics around their use. Post-incident investigations often conclude that a system is infected with malware, but may not uncover that an exploit was used to download the malware onto the system. As organizations adopt advanced endpoint protection products that block these types of exploits, we expect an increase in awareness and reporting of their prevalence in the threat landscape.

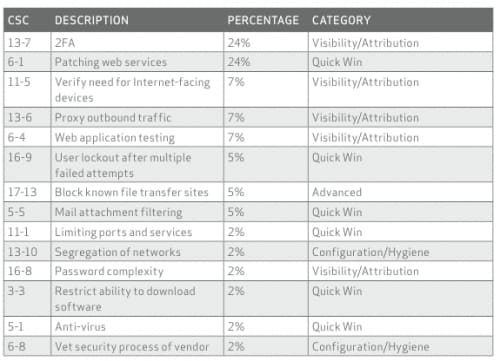

“40% of controls determined to be most effective fall into the quick win category.”

In the summary of this year’s DBIR, Verizon has included a table showing which Critical Security Controls (CSC) would have applied to the incidents they’ve tracked. This table is telling because most of these controls are relatively simple for an organization to deploy, especially if they have the right security platform already deployed. If organizations deployed just the “quick wins,” the volume of breaches could decline substantially by the time next year’s report is released.

Image 1. SANS Critical Security Controls mapped to incidents observed by Verizon, which can be used as a guide for implementing foundational security controls with the most impact. Source

Overall, Palo Alto Networks and the Unit 42 threat intelligence team are honored to be included in the 2015 DBIR. We firmly believe that sharing intelligence on adversaries, campaigns, and attacks is one of the most effective tools we have to raise the cost of a successful breach for attackers. The more organizations that have relevant and timely intelligence, the harder it will become for attackers to compromise them. We look forward to sharing more threat intelligence and research throughout the security community, including in our role as a founding member of the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.