This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

The Hancitor downloader has been relatively quiet since a major campaign back in June 2016. But over the past week, while performing research using Palo Alto Networks AutoFocus, we noticed a large uptick in the delivery of the Hancitor malware family as they shifted away from H1N1 to distribute Pony and Vawtrak executables. In parallel, we received reports from other firms and security researchers seeing similar activity, which pushed us to look into this further.

Figure 1 AutoFocus view of new sessions of Hancitor since July 2016

The delivery method for these documents remained consistent to other common malicious e-mail campaigns. Lures contained subjects related to recent invoices, or other matters requiring the victim’s attention, such as an overdue bill. These lures were expected, until we started digging into the actual documents attached and saw an interesting method within the Visual Basic (VB) macros in the attached documents used for dropping the malware.

This blog will review in detail the dropping technique, which isn’t technically new, but this was the first time we’ve seen it used in this way. The end goal is to identify where the binary was embedded, but we’ll cover the macro and the embedded shellcode throughout this post.

The Word Document

For this section, we’ll be looking at the file with a SHA256 hash of ‘03aef51be133425a0e5978ab2529890854ecf1b98a7cf8289c142a62de7acd1a’, which is a typical MS Office OLE2 Word Document with your standard ploy to ‘Enable Content’ and run the malicious macro.

Figure 2 The ploy used by the malicious document

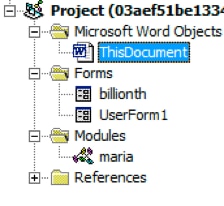

Opening the Visual Basic editor up, we can see two forms and a module for this particular sample.

Figure 3 VBProject components

The Malicious Macro

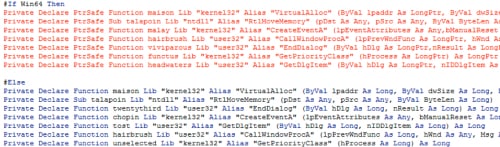

Visual Basic can directly execute Microsoft Windows API calls, which allows it perform a number of interesting functions -- exactly what this VB code is doing.

Figure 4 Microsoft Windows API calls within VB code

As we can see, the macro includes logic to determine the architecture of the system it’s running on and has the ability to execute correctly on either 32-bit or 64-bit platforms. The primary calls of interest for us will be VirtualAlloc(), RtlMoveMemory(), and CallWindowProcA().

When we originally started looking at this sample, we were mainly interested in where the payload was being stored, so we began debugging the macro to understand how it functions. The payload in question is base64-encoded and embedded within a form in the VBProject as a value of the ‘Text’ field on the ‘choline’ TextBox.

As a side note, what is really interesting is that the authors went through the trouble to actually write their own base64 decoder purely in VB. We’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader to dig into that but it’s a good overview of how base-N encoding works; the entire ‘maria’ module within this macro is the base64 decoder.

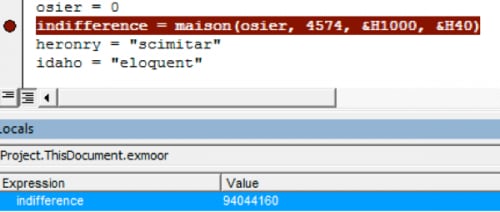

The macro base64 decodes the payload into a local byte-array and then we come to our first API call, VirtualAlloc().

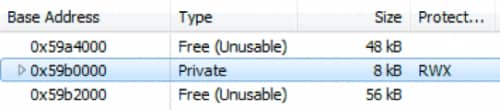

Figure 5 Memory page being allocated

The call commits specific pages of memory with read, write, and executable (RWX) permissions at 0x59B0000.

Figure 6 New memory page with RWX permissions

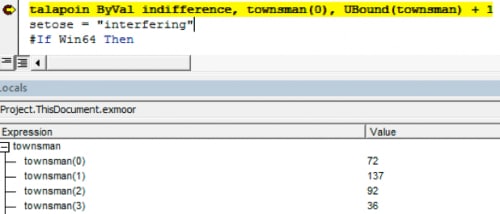

Afterwards, the VB macro continues to setup the next call to RtlMoveMemory and then calls it with the location of the memory from the previous call and our base64 decoded byte array.

Figure 7 Base64-decoded byte array

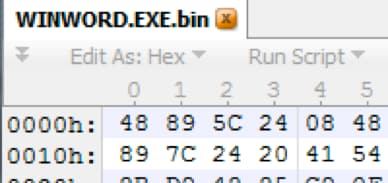

We can quickly validate by dumping that region of memory in our WINWORD.EXE process and comparing transferred bytes.

Figure 8 Confirming bytes match from dumped memory

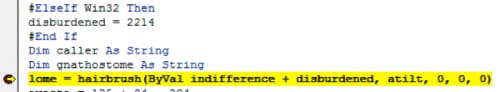

Now that our code has been copied to in executable memory, the macro sets up the last API call for CallWindowProcA(). The first value supplied to this call is our memory offset +2214, which is a function pointer within this code, and the second is a string of the path to our file for a handle. These actions redirect code execution to shellcode.

Figure 9 Passing execution to the shellcode

The Shellcode

If we attach to WINWORD.EXE and break on the offset of our memory location +2214 (0x8A6), the entry point of the shellcode, we can validate program execution shifts to this code path.

Figure 10 Validating shellcode is executing

From here, the shellcode gets the address for LdrLoadDLL() function, which is similar to LoadLibraryEx(), by enumerating the Process Environment Block (PEB) and then begins to hunt for the functions it will use within kernel32.dll.

The values for the functions it’s looking for, along with other values, are embedded into the shellcode and built on the stack for later usage.

Figure 11 Embedded data in shellcode

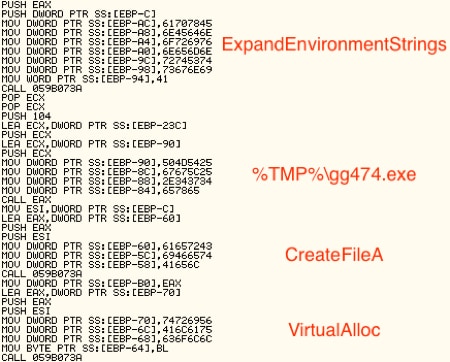

Following these sets of encoded names, we can see the shellcode is interested in the following syscalls: CloseHandle(), ReadFile(), GetFileSize(), VirtualFree(), VirtualAlloc(), and CreateFileA(). For each API call, it looks up the address of the function and stores it on the stack.

Next, the shellcode calls CreateFileA() on the Word document and receives a handle back, which it passes to GetFileSize() for the file size, that is then subsequently passed to VirtualAlloc() to create a section of memory for the file contents (0x2270000). Finally, it reads in the file to that memory location and closes the handle.

Figure 12 Egg hunting by the shellcode

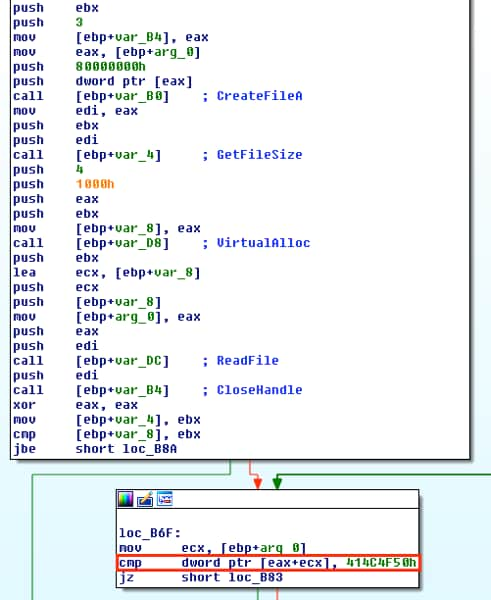

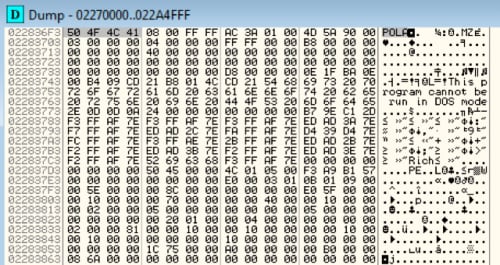

Once it has the copy loaded into memory, it begins a process of hunting through memory for the magic bytes 0x504F4C41, which we can see is located at 0x022836F3 in our new memory page.

Figure 13 Egg located

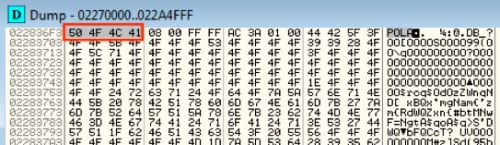

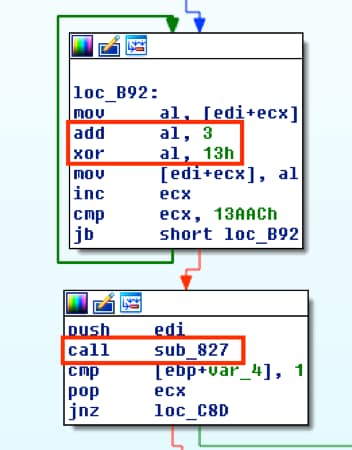

Now that we’ve found what’s likely to be our binary, the last step is to just decode it. Looking at the shellcode, we can see that it will add 0x3 to each byte starting at 0x22836FF, in our example, and then XOR it by 0x13, as shown below.

Figure 14 XOR decrypting

Once the counter reaches 0x13AAC (80556), it begins a series of sub-routines to manipulate each byte and decrypt the binary. If we set a breakpoint after the decryption routine and check our memory location, we can see that the binary is decoded and can now be dumped for further analysis. The MZ and PE headers can be seen in the following dumped memory.

Figure 15 Decoded binary

For this particular campaign run with this dropper, it places the binary in the %TMP% directory before launching it, which then ends up writing itself to ‘%SYSTEMROOT%/system32/WinHost.exe’.

At this point, the Hancitor downloader has been fully loaded on the victim’s machine, where it will proceed to perform additional malicious activities.

Conclusion

Macro-based techniques are quite common, but the technique being used here with the macro dropper is an interesting variation. From the encoded shellcode within the macro and using native API calls within VB code to pass execution to carving out and decrypting the embedded malware from the Word document, it’s a new use of Hancitor that we’ll be following closely. .

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from the dropper detailed throughout this blog and its contained Hancitor payload. You can continue to track this threat through the AutoFocus Hancitor tag. Additionally, all Hancitor downloader samples are identified as malicious in WildFire. Domains used by Hancitor are also categorized as malicious.

Acknowledgements

For more analysis of the Hancitor payload, please see this write-up by Minerva Labs.

Indicators of Compromise

Below are some of the most common observed e-mail subjects and file names seen in the latest campaign this week from over 380,000 sessions. Patterns substituted with regex or representation.

Email Subjects

<domain> invoice for <month>

levi.com invoice for august

<domain> bill

<domain> deal

<domain> receipt

<domain> contract

<domain> invoice

metlife.com bill

metlife.com deal

metlife.com receipt

metlife.com contract

metlife.com invoice

File Names

artifact[0-9]{9}.doc

bcbsde.com_contract.doc

contract_[0-9]{6}.doc

generic.doc

price_list.doc_[0-9]{6}.doc

report_[0-9]{6}.doc

In addition, we observed these C2 calls out during analysis, which can be detected at your perimeter by the use of ‘/(sl|zaopy)/gate.php’.

hxxp://betsuriin[.]com/sl/gate.php

hxxp://callereb[.]com/zapoy/gate.php

hxxp://evengsosandpa[.]ru/ls/gate.php

hxxp://felingdoar[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://gmailsign[.]info/plasma/gate.php

hxxp://hecksafaor[.]com/zapoy/gate.php

hxxp://heheckbitont[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://hianingherla[.]com/sl/gate.php

hxxp://hihimbety[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://meketusebet[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://mianingrabted[.]ru/zapoy/gate.php

hxxp://moatleftbet[.]com/sl/gate.php

hxxp://mopejusron[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://muchcocaugh[.]com/sl/gate.php

hxxp://ningtoparec[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://nodosandar[.]com/ls/gate.php

hxxp://nodosandar[.]com/zapoy/gate.php

hxxp://ritbeugin[.]ru/ls/gate.php

hxxp://rutithegde[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://surofonot[.]ru/sl/gate.php

hxxp://uldintoldhin[.]com/sl/gate.php

hxxp://unjustotor[.]com/sl/gate.php

hxxp://wassuseidund[.]ru/sl/gate.php

The below Yara rule can be used to detect this particular dropper and technique described throughout this blog.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

rule hancitor_dropper : vb_win32api { meta: author = "Jeff White - jwhite@paloaltonetworks @noottrak" date = "18AUG2016" hash1 = "03aef51be133425a0e5978ab2529890854ecf1b98a7cf8289c142a62de7acd1a" hash2 = "4b3912077ef47515b2b74bc1f39de44ddd683a3a79f45c93777e49245f0e9848" hash3 = "a78972ac6dee8c7292ae06783cfa1f918bacfe956595d30a0a8d99858ce94b5a" strings: $api_01 = { 00 56 69 72 74 75 61 6C 41 6C 6C 6F 63 00 } // VirtualAlloc $api_02 = { 00 52 74 6C 4D 6F 76 65 4D 65 6D 6F 72 79 00 } // RtlMoveMemory $api_04 = { 00 43 61 6C 6C 57 69 6E 64 6F 77 50 72 6F 63 41 00 } // CallWindowProcAi $magic = { 50 4F 4C 41 } // POLA condition: uint32be(0) == 0xD0CF11E0 and all of ($api_*) and $magic } |

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.