We continue our series on using IDAPython to make things easier for reverse-engineers by tackling a problem malware analysts deal with on an almost daily basis: extracting embedded executables. Malware will often store embedded executables in a number of ways. Some examples include attaching these files in the file’s overlay, including them as a PE resource, or storing them in a buffer within the malware.

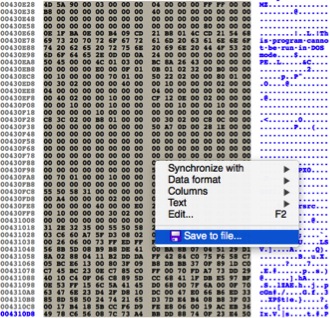

When such a situation arises, malware analysts have a few options. They could dynamically run the sample and break after the file is written/extracted. Alternatively, if the file is stored in a resource section, they could use a utility such as CFFExplorer to extract the resource. In IDA Pro, an analyst can also highlight the necessary data in the hex view, and right-click ‘Save As’ in order to extract this data.

Figure 1 Extracting data in IDA Pro

Figure 1 Extracting data in IDA Pro

While many of these options are feasible, each presents its own limitations. The ability to automatically detect and extract these embedded executables would be useful in saving the analyst precious time. To accomplish this, we’re going to use a combination of IDAPython and a third-party library named ‘pefile’. This particular situation poses a few unique challenges:

- We must enable third-party Python libraries installed with PIP in the IDA Pro environment.

- Embedded executables have to be identified.

- The size of any discovered executables has to be calculated in order to extract them.

Let’s tackle these challenges one at a time.

Enabling Third-Party Python Libraries in IDA Pro

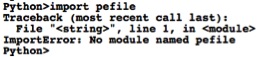

Enabling third-party Python libraries that were installed with PIP in IDA Pro poses an interesting challenge. With no modifications, an analyst is unable to load third-party libraries, such as pefile, in the IDAPython interpreter, as seen below.

Figure 2 Failed attempt at loading pefile in IDAPython

To correct this, we must add PIP’s ‘site-packages’ directory to the Python environment variable. This variable can be viewed using the following code:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

import sys print sys.path Result: ['/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python27.zip', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/plat-darwin', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/plat-mac', '<Truncated>'] |

To include PIP-installed libraries, we can simply append the ‘site-packages’ directory to this array prior to our ‘import pefile’ statement. This solution isn’t elegant, as it requires the analyst to manually determine the ‘site-packages’ directory, but I haven’t found a platform-independent solution to help (if you know of one, feel free to comment below or send me a tweet @jgrunzweig). After including the necessary code, we’re able to load the pefile library.

![]() Figure 3 Successful loading of the pefile libary in IDA Pro

Figure 3 Successful loading of the pefile libary in IDA Pro

Identify Embedded Executables

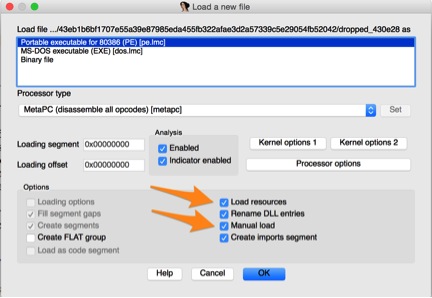

To discover if the malware contains any embedded executables, we can perform a binary search against a known string in the MZ header. Please note that the analyst must ensure that the ‘Load resources’ button is checked upon loading the file to see any data that is stored as a resource. Additionally, in the event that an embedded file is included in the overlay section, the ‘Manual load’ button must be checked in order to see this data in IDA Pro.

Figure 4 Checked options to see various data in IDA Pro

Figure 4 Checked options to see various data in IDA Pro

Now that we have the necessary information loaded into IDA Pro, we can perform the task of searching through the data to identify PE32 files. There are a couple ways that we could approach this, but I chose to search for the following static message that appears in every MZ header.

!This program cannot be run in DOS mode.

To find all occurrences of this string in IDA, we can make use of the FindBinary() function with a loop that will allow us to iterate through every instance of a binary string. The following code can be used to accomplish this in a generic manner:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

def find_string_occurrences(string): results = [] base = idaapi.get_imagebase() + 1024 while True: ea = FindBinary(base, SEARCH_NEXT|SEARCH_DOWN|SEARCH_CASE, '"%s"' % string) if ea != 0xFFFFFFFF: base = ea+1 else: break results.append(ea) return results |

While finding the MZ header string provides a good indication that we’ve found a PE32 file, we need to verify by also looking for the iconic ‘MZ’ characters that are found at the beginning of the MZ header. Since the string we previously searched for is at a static offset, we can simply check for the presence of ‘MZ’ at the known offset.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

def find_embedded_exes(): results = [] exes = find_string_occurrences("!This program cannot be run in DOS mode.") if len(exes) > 1: for exe in exes: m = Byte(exe-77) z = Byte(exe-76) if m == ord("M") and z == ord("Z"): mz_start = exe-77 print "[*] Identified embedded executable at the following offset: 0x%x" % mz_start results.append(mz_start) return results |

Stringing this code together allows us to identify all instances of embedded portable executables within IDA Pro.

![]() Figure 5 Identifying embedded executables in IDA Pro

Figure 5 Identifying embedded executables in IDA Pro

Determining Executable Size

To determine the size of the identified embedded executable, we’re going to make use of the pefile Python library that was previously mentioned. This library will allow us to parse the various executable headers, which will in turn allow us to calculate the PE’s size. To accomplish this, we will add the ‘SizeOfHeaders’ parameter from the Optional Header, along with every section’s ‘SizeOfRawData’ field. The following code will read in the first 1024 bytes of the identified embedded executable, parse this data using pefile, and tally the various size fields.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

def calculate_exe_size(begin): buff = "" for c in range(0, 1024): buff += chr(Byte(begin+c)) pe = pefile.PE(data=buff) total_size = 0 # Add total size of headers total_size += pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.SizeOfHeaders # Iterate through each section and add section size for section in pe.sections: total_size += section.SizeOfRawData return total_size |

Finally, we can use this total size value to extract the executable data and write it to a file of our choosing.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

def extract_exe(name, begin, size): buff = "" for c in range(0, size): buff += chr(Byte(begin+c)) f = open(name, 'wb') f.write(buff) f.close() |

Conclusion

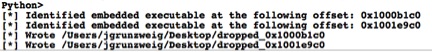

Putting all of this together, we come up with the following script. Running this on an example malware sample yield the following:

Figure 6 Result of running IDAPython script

Figure 6 Result of running IDAPython script

As we can see, we can now automatically extract PE files from IDA Pro. With minor modifications, this approach can certainly be applied to other file types as well. I hope this short tutorial helps expose readers to the many possibilities and capabilities the IDAPython bindings bring to reverse engineers.

Read previous entries in this series on IDAPython:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.